Steven Roger Fischer writes on the etymology of the verb to read in his A History of Reading:

Many early mediæval Angles, Saxons and Jutes read in runes, though some of them also commanded the Latin tongue and script. The Old English word rædan (originally meaning ‘consider, interpret, discern’ and so forth) came to mean not only ‘read’, but also ‘advise, plan, contrive, explain’. When still on the Continent these German tribes had encountered Roman writing, which, they perceived, required ‘discerning’. So, through transference and figuration, rædan came to mean also ‘interpret signs or marks’, then eventually ‘peruse and utter in speech’. (145)

Besides the Old English rædan, a lot of words related to reading have their root in the Latin verb legere ‘to read’: lector, lecture, legend, lexicon. The Roman languages and German also go back to the Latin: German lesen, French lire, Spanish leer and Italian leggere.

What’s interesting is that the Old English rædan emphasises the deciphering of symbols, whereas the Latin derives from the Greek legein ‘to say’, stressing the fact that reading represents speech. I have had an opportunity to notice this difference recently when I read Bernhard Schlink’s novel The Reader, whose German title Der Vorleser translates as “the person reading aloud to someone else”.

Schlink’s book broaches the problem of reading and interpretation, in this case concerning the experience of the Holocaust. The novel’s female protagonist, Hannah Schmitz, delights in her lover’s reading aloud to her from plays and novels. A former warden at Auschwitz, Hannah remains (both willfully and involuntarily) ignorant of her past crimes. Only when she starts reading herself about the the atrocities of Holocaust does she begin to question and interpret her actions. Reading for herself helps Hannah make sense of her own life and, ironically, speaks louder than the stories she listened to.

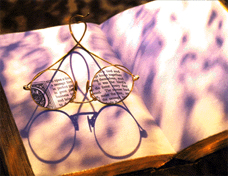

Fischer, Steven Roger. A History of Reading. London: Reaktion Books, 2003. The picture is from Alberto Manguel’s A History of Reading.

Very interesting that there are these two different ways of describing reading. I wonder if it has to do with the difference between logographic and phonographic written language. The former has to be interpreted before you can do anything with it but the latter can be spoken even without understanding the meaning.

Love the image, by the way.

The picture is nifty, isn’t it, as is Manguel’s History of Reading, by the way. At times, it’s not very scholarly, more personal, but there lies its charm.

Your comment on logographic versus phonographic script could be spot on. After all, the Celts, Angles, Saxons and Jutes read in runes — a logographic script, for all I know — before they “eventually fell to the supremacy of the Latin alphabet, the vehicle of the all-powerful Roman Church” (Fischer, 144). As I mentioned in an earlier post on the reading brain, the development of phonographic script was a crucial invention in Western society, and I am convinced it influenced our understanding of language, interpretation and speech as well.

Hi! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on.

Any suggestions?